Balfour or Against?

Reviewed by: Samuel Warshaw

The centenary of the Balfour Declaration has stimulated a flurry of articles, radio and television programmes and commemorative events in both Jewish and wider circles, far more than the concurrent quincentenary of the Reformation, demonstrating the perhaps somewhat surprising degree of significance that is still attached to this 125-word, rather ambiguous note of no formal legal standing. The world remains obsessed with Israel, and her never-ending conflict with the Palestinians, and how it all came to pass.

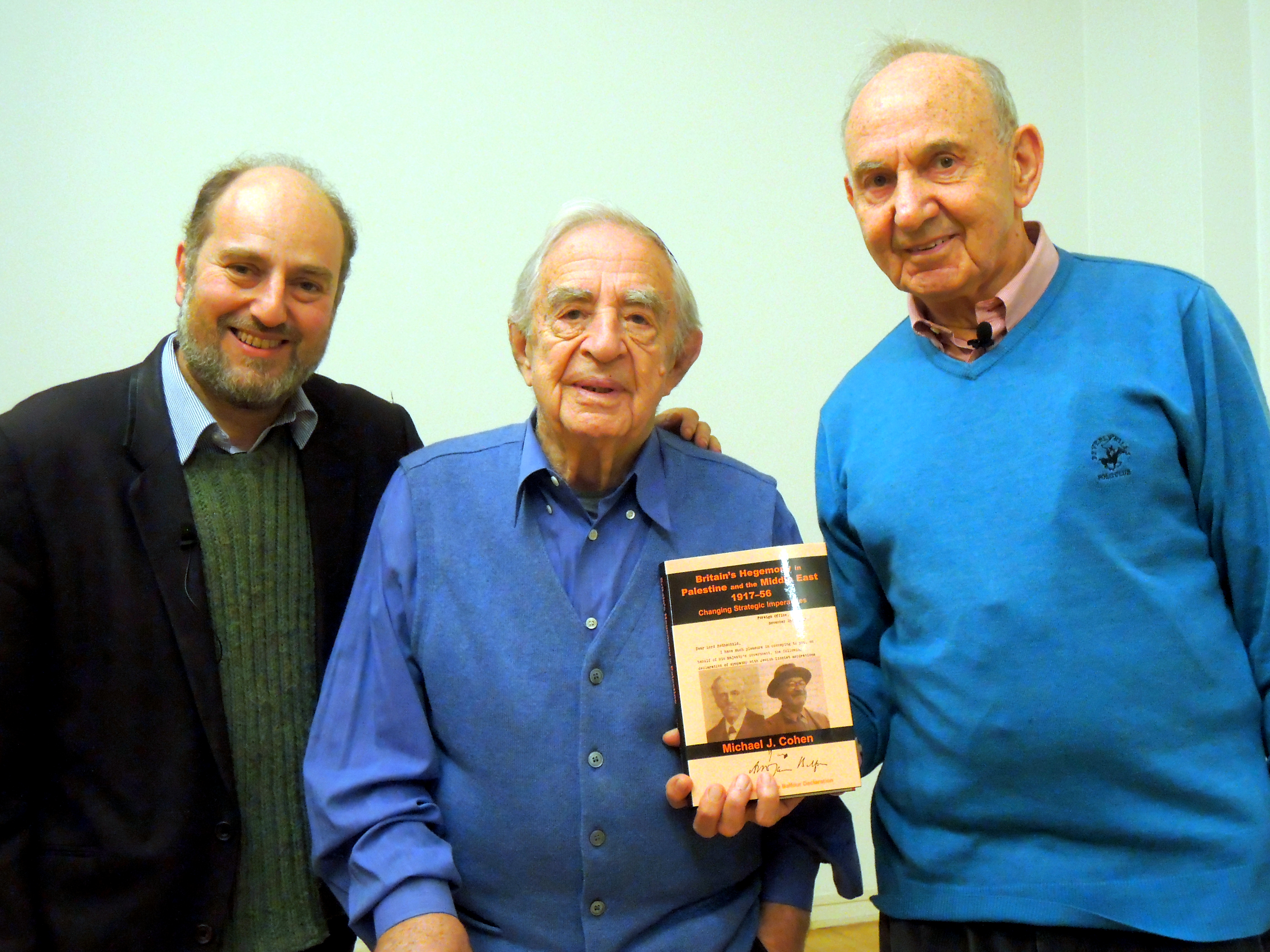

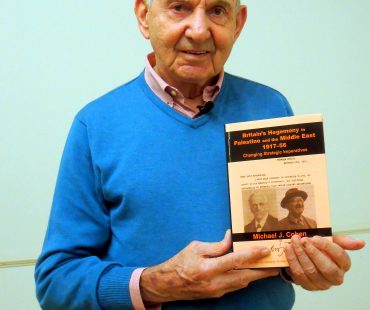

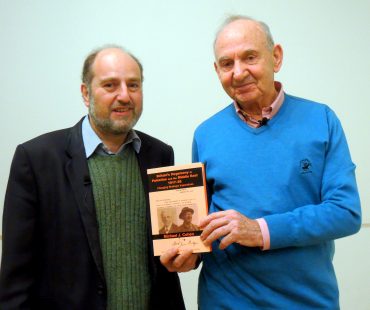

Spiro Ark’s as ever illuminating contribution to this commemorative fervour was a lecture on British motivations in the business and beyond by Professor Michael Cohen, Professor Emeritus at Bar Ilan University, author of numerous books, including Britain’s Hegemony in Palestine and the Middle East 1917-56, and student of the late Eli Kedourie, one of the first historians of this period, who devastatingly skewered Lawrence of Arabia-style, Orientalist views of the Middle East.

“It is a rather cynical story,” explained Cohen. It certainly was in his telling, which dismissed any suggestion of high-minded intentions on the part of the British, and brought into focus a side of the story that is often neglected in the heroic and romantic narrative of the ascent of the Zionist movement that many of us grew up on.

Held in the congenial hall of the Central Synagogue on Halloween, and chaired with exemplary élan and erudition by the distinguished journalist and Middle East expert Lawrence Joffe, Cohen’s fascinating and well-structured lecture took us on a gallop through British government policy on Palestine from shortly before the issuing of the Balfour Declaration to the eve of the Second World War.

Cohen dated the awakening of serious British interest in control of Palestine to 1915 when a tiny Turkish force led by German officers succeeded in crossing the Sinai Desert to reach the Suez Canal. The canal was Britain’s lifeline to India, the jewel in the crown of the empire, and other imperial possessions in the East, cutting journey times by half. Though the incursion had no military significance and was quickly mopped up by the British troops in Egypt, the event apparently shocked the British, for whom it had been an article of faith that the Sinai Desert was impassable, out of all proportion, and suddenly they grew markedly interested in holding more of the Levant, including Palestine, as a wider buffer zone to protect the canal. The opportunity came as the Ottoman front disintegrated during the First World War. By the time Allenby walked into Jerusalem as its humble conqueror in the carefully stage managed events of 11th December 1917, the Balfour Declaration – that characteristically British document, in its patrician format of an amicable and slightly vague missive from one lord to another - had been sent six weeks earlier from Balfour to Rothschild, expressing government support for the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.

Cohen attributed support for Zionism purely to British self-interest, and to the British perception and, he maintained controversially, reality of Jewish global financial power and influence. An immediate consideration was to encourage the USA to declare war on Turkey (America had already entered the war in April, but only against Germany); the British government believed that the knowledge that, with British support, the defeat of Turkey would boost the chances of the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, would spur American Jews in and close to the US government to put pressure on America to enter the war.

In evincing that there was a sound basis for such a belief, Cohen pointed to the role of Jews in the US administration in persuading a dubious President Wilson to agree to the Balfour Declaration, and set great store by an episode when Weizmann, with British government assistance, intercepted, in Gibraltar, the Jewish former American ambassador to Turkey Henry Morgenthau, who had been sent by the American government to try to negotiate a peace deal with the Turks. Weizmann persuaded his co-religionist Morgenthau to abandon his mission, so as not to damage the chances of the establishment of a Jewish state (there had been attempts since Herzl to persuade the Turks to look favourably on Jewish settlement, but without success).

Throughout, British government support for the Zionists was given in the teeth of prevailing anti-Zionism and antisemitism in British society and periodic outraged editorials in most newspapers. There was widespread sympathy for the Arabs and even members of the government who agreed to the policy often did so most reluctantly, such as Lord Curzon, the former Viceroy of India who warned his cabinet colleagues that the Arabs would not be content to be expropriated and turned into hewers of wood and drawers of water for the Jews.

If the British were not wrong about Jewish influence, where they were wrong, Cohen pointed out, was in the belief that Zionism was popular with most Jews, influential or otherwise. They should perhaps have known better as Jewish members of the cabinet, such as Edwin Montagu, Secretary of State for India (whose father, née Montagu Samuel, later the first Baron Swaythling, had Anglicised himself by transposing his first and surnames, prompting an antisemitic limerick from Hilaire Belloc) were amongst the strongest opponents of the Balfour Declaration. These anti-Zionist Jews averred that it queered their pitch by putting in doubt their national loyalties, and it was they who were queasy at the idea of any precedent of disenfranchisement being set, when their own enfranchisement had only come recently, and been so hard-won. So they insisted on the inclusion of the second part of the declaration, that “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.” In this, opined Cohen, “they scored an own goal against Zionism which many Jews today choose to forget.” (Certainly the misconception among the ignorant of anything like unanimous support for Zionism historically needs correction. And Jewish hostility towards or misgivings about Zionism among the comfortable classes is well-documented. It was by no means universal though; after all, the most enthusiastic cabinet support for the Balfour Declaration came from Edwin Montagu’s [non-appellatively-transposed] cousin Herbert Samuel, later the first High Commissioner of Palestine. While there the poor man found himself reviled by both his fellow Jews and the Arabs. And one wonders how Cohen can be quite so sure that Zionism only garnered minority support among poor Russian Jews?)

After the Great War, with British hold on the area secure, there remained sound realpolitik reasons to support the Jewish settlement in Palestine. For one thing, the Jewish settlement was leading to a flow of money from (mainly American) Jews, and the Jews were building up the economy, meaning Palestine was one of the few places where, in the twilight years of the British Empire, the elusive goal that the Empire should pay for itself was met.

On the other hand, steps were taken to attempt to appease Arab disquiet at the influx of Jews, and keep them on side (Palestinian nationalism had, of course, barely emerged, and Arabs in Palestine of a political bent generally saw themselves as Southern Syrians). In 1921 Transjordan was hived off from the mandate and presented to Abdullah al-Hussein, in a typically ad hoc fashion at a teaparty by Churchill. However, this was specifically to placate his family and compensate for their loss of Syria, out of which his brother Faisal had just been kicked by the French, having been transplanted there from Western Arabia by the British, and to dissuade him from attacking the French and thereby destabilising the region.

Then in 1922 the government issued the first of its three white papers on Palestine. This limited Jewish immigration to the economic absorption capacity of the territory – the number was agreed twice yearly between the Zionists and the British mandate administration (there were no restrictions though on the few Jews who brought with them wealth above a certain threshold). At the same time the British also, in a disastrous attempt to co-opt the young Arab extremist leading the campaign against Jewish settlement, Amin al-Husseini, created two prestigious offices for him, including making him Mufti of Jerusalem (he would soon restyle himself Grand Mufti), and gave him an enormous budget – the appalling repercussions of which echo today.

Following the Arab riots of 1929 – which took the British and Zionists by surprise, and, had not they been suppressed by the authorities, would probably, argued Cohen, have marked the end of the Zionist settlement – the British government issued a second white paper, in 1930, changing the conditions on Jewish immigration. Under the new terms, Jews would only be allowed to enter Palestine at times of no Arab unemployment. This would effectively have halted the growth of Jewish settlement but the white paper was never enacted in law, following a successful lobbying campaign by Zionists. Cohen argued that the government was persuaded to abandon the measure because of fear of financial pressure global Jewry could exert on Britain if antagonised – and again controversially argued that, though exaggerated, “fear of Jewish influence… had a lot of weight to it.” The Wall Street Crash had recently occurred, the fall-out of economic depression in America was spreading, and there was a risk the US might call in its loans to Britain. Ramsay MacDonald’s government equated Jews with banking and capitalism and calculated they needed Jewish money to keep Britain afloat. Some 200,000 Jews were therefore able to enter Palestine between 1931 and 1935, doubling the Jewish population.

But in the mid-30s British policy of currying favour with the Jews began to disintegrate. As the League of Nation showed its impotence in Abyssinia in 1935 and Spain in the following years, and the prospect of another war with Germany loomed, the British decided it was imperative to court the Arab world. At best, they hoped to form a military alliance that held sway over a wide territory and gave access to vital oil, and at the least to ensure Arab neutrality and dissuade them from allying with Germany. This over-rode policy considerations that favoured Jewish settlement and led to the third, and in Jewish circles, infamous, white paper of 1939, which pledged that an Arab state would be established in Palestine within 10 years. Most devastatingly, on the eve of war and at the moment Europe’s Jews needed sanctuary as never before, they restricted Jewish immigration to 75,000 over the following five years (a figure calculated to ensure the 2:1 demographic ratio of Arabs to Jews in Palestine would remain unchanged). In fact, British bureaucracy dragged its feet in releasing immigration permits such that not even that number were allowed to enter. In this indelibly shameful decision, which signed the death warrant of the Jews of Europe, the British government’s uneasy endorsement of Zionism came to an end.

The lecture was followed by a vigorous question-and-answer session, notably including exchanges on both the McMahon-Hussein correspondence and Faisal al-Hussein’s overtures to the Zionists. Cohen rather dismissed the political significance of the McMahon-Hussein correspondence, in which, shortly before the Balfour Declaration, the British consul in Cairo Henry McMahon seems to suggest to Hussein ibn Ali, the Sharif of Mecca (and father of Faisal and Abdullah) that the British would hand him Palestine in exchange for military support against the Turks to take the Dardanelles. This is often characterised as an Arab mirror of the Balfour Declaration and upheld as a canonical example of British duplicity in promising the same land to two peoples. But Cohen pointed out that the McMahon correspondence, unlike the Balfour Declaration, was never discussed at British cabinet level. No agreement was concluded, the territory to which it refers is unclear, and a letter written by McMahon himself says there was no intention of fulfilling the British side of the bargain and it was merely a ploy to encourage Arab support.

A member of the audience raised the point that Faisal looked on the correspondence as important and cited it in his dealings with Weizmann and the other Zionists, which famously culminated in an agreement that he would welcome Jewish territorial control in Palestine while the Zionists would support Arab self-determination in Syria. Cohen dismissed out of hand Faisal’s dealings with the Zionists as irrelevant, because French imperial ambitions put paid to Faisal’s plans, and his authority in the Arab world was not universal and on the wane. Nevertheless, it does seem one of the great, heartrending what-might-have-beens of modern Arab and Jewish history.

Indeed, Cohen obviously sees it as his role to undertake long-overdue myth-busting, but perhaps occasionally busts too far. The significance of Christian Zionism as a motivation of members of the British government has doubtless often been greatly over-egged, and Cohen shot it out the water. In fact, he provided manifold examples of casual antisemitism among those, such as Lloyd George, sometimes deemed to have harboured romantic religious prejudice in favour of the Jews. His dismissal of the significance of the British Establishment’s favourable disposition towards Weizmann, partly as a result of his contribution to the war effort, is less convincing. The charismatic Weizmann’s chemical advances in acetone production, used for munitions, was of great value to Britain, as Lloyd George and other British politicians involved attested. When political questions are delicately balanced, personal relationships can make the difference.

Cohen ended by proferring a thought on the dismal Israeli-Palestinian stalemate today, quoting Weizmann, that it “is not a conflict of right and wrong but one of two rights and two wrongs.” He added that the Jews have been unfortunate in having an uncompromising opponent (some hardbitten cynics may argue the reverse) but lucky in having one that has been relatively easy to beat – but that the possibility of keeping a lid on the situation is now coming to end, though most Israelis, sadly, do not see it. Here’s hoping that by the 200th anniversary this curious foundational document will not be evoking such raw, antithetical emotions. And as an Englishman one can take comfort, I suppose, that perfidious Albion was still never quite as perfidious in the Middle East as the French.

Professor Michael Cohen is Emeritus Professor of History at Bar-Ilan University. He was a Visiting Professor at the Universities of Duke, Chapel Hill, Maryland, San Diego and British Columbia in North America and the London School of Economics; he was elected to be a Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, in 1998. Read more of his writing on this topic HERE. His latest book, which formed the basis of the lecture he gave us, is Britain's Hegemony in Palestine and in the Middle East, 1917-56: Changing Strategic Priorities (2017).